This is a story from my Undercurrents collection. Undercurrents takes real headlines (the link is included for you to read) and exposes a hidden narrative lurking beneath the surface.

HEADLINE: “Bin strike reaches one-year mark with no end in sight” SOURCE: BBC News, 6 January 2026

You’ve been on the picket line for exactly one year today. Three hundred and sixty-five days standing outside the depot on Lifford Lane, watching agency workers cross to collect bins you should be collecting. You’re a Waste Recycling and Collection Officer—or you were, until Birmingham City Council decided your role didn’t exist anymore.

Your name is Danny McKenzie. You’ve worked refuse collection for fourteen years. You remember the 2017 strike, when they created the WRCO role specifically to end that dispute. Good money, £40,000 a year, safety expertise for a dangerous job. You’d trained for it, earned it. Then last January, the council announced they were eliminating the position entirely. Just like that.

Unite said the council was claiming it would save £8,000 per worker, prevent equal pay claims. The council said only seventeen workers would lose that much, and they’d have six months’ pay protection. You did the maths. Seventeen workers times £8,000 times the number of years until retirement. Someone was lying about the numbers.

But that wasn’t what kept you on the picket line.

It was the commissioners.

They’d arrived in 2024, sent by the government to oversee Birmingham’s finances after the council declared effective bankruptcy—something about a £760 million equal pay settlement. Except in October, you’d read that the actual figure was a fraction of that. Someone had been using inflated numbers to justify the intervention.

You started keeping notes in March, when the strike went indefinite. Small things that didn’t quite fit. The way negotiations kept collapsing at the last minute. The way the council’s offers got worse instead of better. The way wealthy areas got their bins collected by agency workers three times more often than poor areas, despite official routes that should have been equal.

In June, everything changed.

You weren’t in the room, but Danny Wright was—Danny from the union negotiating team. He’d called you that night, voice shaking with exhaustion and relief.

“We got it, McKenzie. The ballpark deal. Joanne Roney agreed to everything. WRCO roles protected, pay maintained, job security guarantees. She’s taking it to the commissioners for approval. Formality, she said. We’ll be back to work by July.”

You’d celebrated that night. Bought a round at the pub. Told your wife the strike was over. Started planning what you’d do with your first proper pay cheque in months.

Then silence.

Days passed. A week. Two weeks. Danny Wright stopped returning your calls. When you finally cornered him at the depot, he looked like he hadn’t slept in days.

“The commissioners vetoed it,” he said quietly. “Said it wasn’t consistent with broader restructuring objectives.”

“What restructuring objectives?”

“That’s what I asked. Roney wouldn’t say. Just kept repeating that her hands were tied, the commissioners had final authority, she couldn’t negotiate beyond their parameters.”

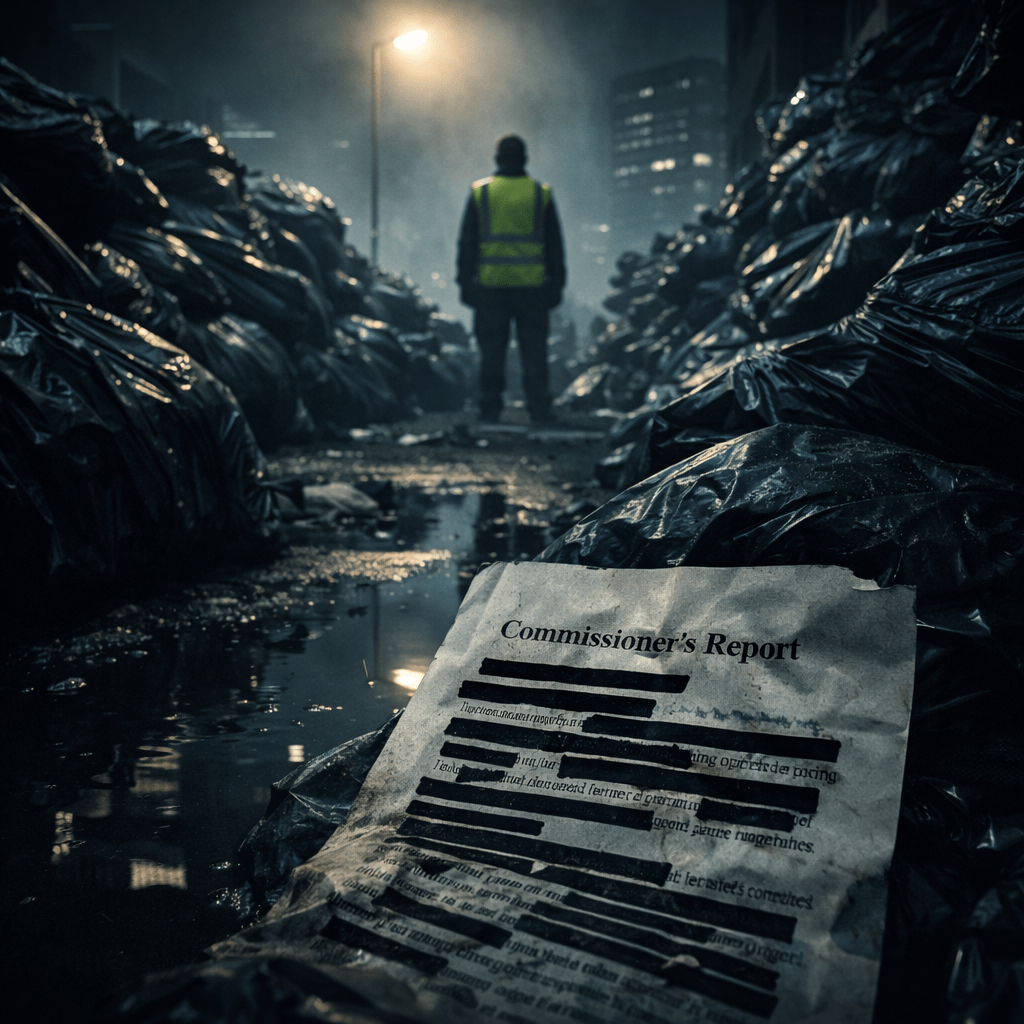

You filed a Freedom of Information request that week. For the commissioners’ report. For their mandate. For any documentation of the “restructuring objectives” that had killed the deal.

Four months later, you received three hundred pages of almost entirely redacted documents. Black bars over everything except dates and the word “Approved” repeated in margins. But you found one unredacted paragraph in a June meeting summary:

“The extended industrial action provides optimal conditions for Phase Two implementation. Resistance remains localised to affected workforce. Public focus on service disruption prevents attention to underlying restructuring. Recommend continued non-settlement until Q4 2026.”

Phase Two of what?

You started researching the commissioners themselves. Three of them, appointed by the Department for Levelling Up. Rachel Adams had a background in municipal restructuring—she’d overseen similar interventions in Northamptonshire and Croydon. Michael Chen specialized in public-private partnerships. The third, Jonathan Blackwood, had no public profile at all before his appointment. No LinkedIn. No professional history. Just a brief government bio listing “extensive experience in strategic transformation.”

You searched Companies House. Blackwood was listed as a director of seven different consulting firms, all registered within the last three years, all with addresses at the same serviced office in London. You checked the clients: councils, housing associations, waste management companies.

One name appeared repeatedly in the contracts: Veolia, the private waste management corporation.

Veolia operated Birmingham’s incinerator. They’d been positioning for years to take over more of the city’s waste services. And now, with the strike dragging into its twelfth month, with recycling suspended indefinitely, with agency workers from Job and Talent being pushed to breaking point, the council was planning a “new waste service” for June 2026.

You obtained a leaked draft of the proposal through a sympathetic councillor. The new service would be “delivered in partnership with private sector operators.” Veolia’s logo was watermarked on every page.

In November, the agency workers voted to strike themselves. Eighteen out of twenty-two Unite members walked out, citing bullying, harassment, and impossible workloads. You’d talked to some of them. They described performance monitoring that tracked every second, quotas that required skipping designated routes to meet targets.

“Which routes?” you’d asked.

Always the same ones. Sparkhill, Small Heath, Ladywood—the inner city areas where complaint rates were lowest. Where people had learned that complaining did nothing. Where the rubbish had been piling up for months while Harborne and Edgbaston stayed pristine.

You mapped it. The areas with the worst uncollected rubbish were the same areas targeted for “regeneration” in council documents from 2023. The same areas where property values had been deliberately suppressed through service degradation. The same areas where developers with links to council contractors had been quietly buying up land.

The pattern was too clean. Too systematic.

In December, you met with three other striking workers in the back room of a pub in Digbeth. You showed them everything: the commissioners’ redacted reports, Blackwood’s corporate connections, the Veolia contracts, the regeneration maps, the property transactions.

“They’re using the strike,” you said. “Keeping it going deliberately. The commissioners vetoed the ballpark deal because the strike creates the conditions they need. Service collapse justifies privatisation. Unequal collection patterns make certain areas look ‘failed’ and ripe for regeneration. By the time this ends, half the city’s waste management will be private contracts, property prices in the inner city will be rock bottom, and the areas that vote Labour will have been systematically starved of services until they give up and move.”

“That’s insane,” one of them said. But he didn’t sound convinced.

“Is it? The equal pay crisis that brought in the commissioners—check the timeline. The figure was £760 million in 2023. Then in October 2025, after the commissioners have been in place for over a year, suddenly it’s ‘a fraction’ of that amount. What if the crisis was exaggerated to justify the intervention?”

“Why?”

“Because Birmingham is the second-largest council in the country. If they can force privatisation here, use a strike as cover to restructure an entire city, they can do it anywhere.”

You attended the council meeting on the strike’s anniversary. January 6, 2026. You sat in the gallery watching Joanne Roney answer questions. She looked tired but composed. Doors remained open, she said. The council had made fair offers. Unite was being unreasonable.

“We’re miles apart,” she said, and you heard the resignation in her voice. Or was it relief?

After the meeting, you tried to approach Councillor Jane Jones—one of the few who’d been vocally critical of the council’s approach. She’d called it embarrassing that a Labour council couldn’t negotiate with a union. But her aide intercepted you in the corridor.

“Councillor Jones can’t comment on ongoing industrial disputes.”

“I just want to ask about the commissioners’ role in—”

“The commissioners are here to ensure fiscal responsibility. Nothing more.”

But the aide’s eyes had flicked toward two men in suits standing by the exit. Security, you thought at first. Then you recognized one of them from your Companies House research. A director at one of Blackwood’s consulting firms.

You walked home through the city centre, past streets lined with uncollected rubbish. Past Sparkhill, where a family navigated around bin bags without comment. Past temporary recycling centres with mile-long queues. Past agency workers in new trucks with Veolia logos that hadn’t been there last month.

Your phone buzzed. A text from an unknown number:

“Stop asking questions about the commissioners. This is friendly advice. There won’t be a second warning.”

You deleted it. Kept walking.

That night, you couldn’t sleep. You kept thinking about the timeline. About how perfectly everything had aligned. The exaggerated equal pay crisis. The commissioners arriving with no real oversight. The WRCO role elimination triggering the strike. The ballpark deal that got just close enough to make everyone think resolution was possible, then getting vetoed. The strike extending to exactly the point where privatisation became inevitable, where service inequality became entrenched, where regeneration could proceed without resistance.

What if none of it was dysfunction?

What if all of it was design?

You got up, opened your laptop, started documenting everything you’d found. You’d send it to journalists, to MPs, to anyone who would listen. Someone had to see the pattern.

Your doorbell rang at 2 AM.

Two police officers. There’d been a complaint about threatening behaviour on a picket line. They needed to ask you some questions. No, it couldn’t wait until morning. You’d need to come with them to the station.

You looked past them to the unmarked car idling at the kerb. Not a police vehicle. The driver’s face was obscured, but you could see the outline of someone in the back seat.

“I want to call my union rep,” you said.

“Of course. You can do that from the station.”

You never made it to the station.

The next morning, Unite reported that Danny McKenzie had resigned from the picket line, citing personal reasons. He’d accepted a position with a waste management contractor in Scotland. Immediate start. No forwarding address.

The statement was issued by the union, but you’d never resigned. You’d never been offered a job in Scotland. You’d been driven to a motorway service station, met by a man who’d introduced himself as “a friend of the commissioners,” and offered a very simple choice.

Take the job. Stop asking questions. Your family stays safe, your pension gets protected, everything ends quietly.

Or refuse, and discover how many labour laws can be creatively interpreted when someone with government backing decides you’re the problem.

You’d taken the job.

Now, three weeks later, you’re in Edinburgh collecting bins for a private contractor. You don’t talk to the other workers. You don’t look at the news from Birmingham. You definitely don’t check whether the Birmingham strike is still going, whether the privatisation contract was approved, whether the regeneration projects proceeded.

But sometimes, late at night, you think about that redacted paragraph.

“Phase Two implementation.”

Phase Two of restructuring one city.

Or Phase Two of restructuring all of them, one manufactured crisis at a time, one prolonged strike providing perfect cover, one set of commissioners ensuring the pattern spreads.

You’ll never know.

You empty bins now. You don’t ask questions.

The strike will end eventually. Maybe this year, maybe next. The bins will be collected by private contractors. The inner-city areas will be regenerated by developers with the right connections. The commissioners will declare victory over fiscal irresponsibility and move to the next council, the next crisis, the next perfectly timed intervention.

And workers like you, who saw the pattern, who asked the wrong questions, who got too close to understanding how the pieces fit together—you’ll be collecting bins in Edinburgh, or Manchester, or anywhere far enough away that you can’t tell anyone what you figured out.

The Birmingham bin strike reaches its one-year mark with no end in sight.

That’s what the BBC reported.

They didn’t report why there was no end in sight.

They didn’t report who benefits from the lack of ending.

They didn’t report that some strikes aren’t meant to be resolved.

They’re meant to provide cover while cities get restructured beneath them, one bin at a time, until nobody remembers how things used to be.

You empty another bin into the truck.

In Birmingham, the rubbish keeps piling up.

Exactly as planned.

“My thanks to James Steindorff for forwarding me this story link” ~ Seb

Leave a comment